- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

South AmericaShort-eared dog Atelocynus microtis

short-eared dog - © Leite Pitman and Swarner

Amazonian Canids Working Group - Karen DeMatteo and Fernanda Michalski are the coordinators of the Amazonian Canids Working Group. This working group is focused on four species: the short-eared dog, crab-eating fox, bush dog, and South American foxes. Amazonian canids are similar to many carnivores worldwide whose long-term survival is threatened by a variety of direct and indirect threats, including habitat loss, expansion of hydroelectric dams, illegal hunting of prey, and diseases from domestic dogs.

Projects- Camera trap wildlife monitoring in and around Madidi National Park, Bolivia

- Short-eared dog Ecology and Conservation

- Effect of climate change on carnivores in the Amazon

- The elusive short-eared Amazon dog

- Residents of the forest - canids from Amazon

- The Amazon’s short-eared dog was thought to be a scavenger. Now there’s video.

- 2004 Status Survey & Convervation Action Plan - South America

- The ghost dogs of the Amazon get a bit less mysterious

- Rare Amazon jungle dog caught on video

- Short-eared dog? Uncovering the secrets of one of the Amazon’s most mysterious mammals.

- For the Amazon’s rarest wild dog, deforestation is a very real threat.

- Amazing Species: short-eared dog

English: Short-eared Dog, Short-eared Fox, Small-eared Dog, Small-eared Zorro

French: Renard à petites oreilles

Spanish; Castilian: Perro de Monte, Perro de Orejas Cortas, Zorro Negro, Zorro Ojizarco

German: Kurzohrfuchs, Kurzohrhund, Kurzohriger Hund

Portuguese: Cachorro-do-mato-de-orelhas-curtas

Taxonomic Notes

Atelocynus is a monotypic genus. The species has formerly been placed in the genera Lycalopex, Cerdocyon, and Dusicyon. Phylogenetic analysis has shown Atelocynus microtis to be a distinct taxon most closely related to another monotypic Neotropical canid genus, Speothos.

Justification

Although widespread, this species is rare and sightings are uncommon across its range. Although there are indications that the population may be recovering in some areas, with increasing numbers of sightings in recent years, this also reflects a greater number of biologists and tourists in the region and improvements in detection technology such as the use of camera-traps. Given the growing threats of habitat loss (especially due to large-scale conversion currently underway in Amazonia, especially for soybean production), prey-base depletion, and disease transmission from domestic dogs, it is inferred that the species has declined in the region of 20–25% over the past 12 years (estimated generation length = 4 years). The species is therefore listed as Near Threatened, based on approximating listing as Vulnerable under criterion A2.

Geographic Range Information

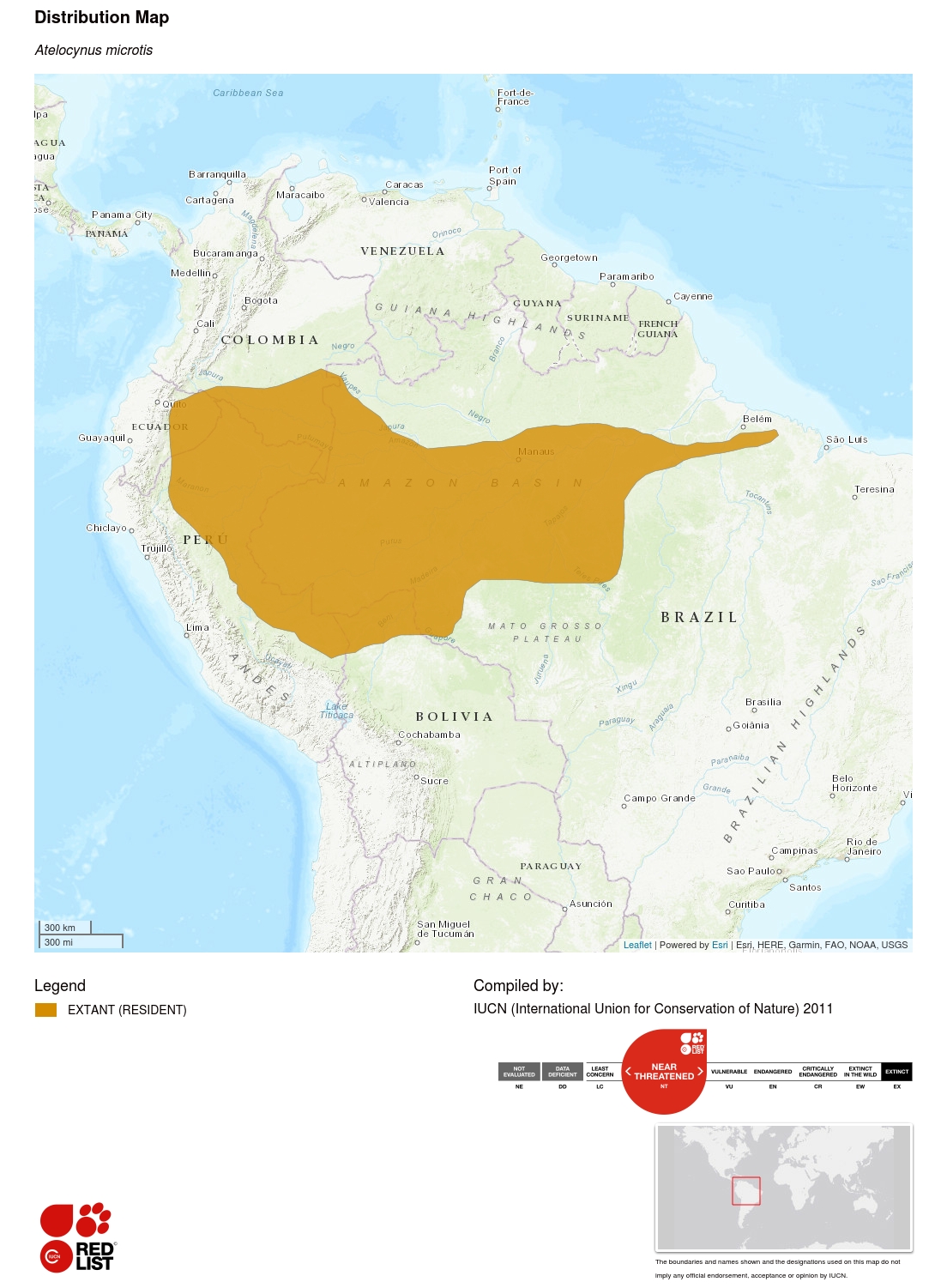

The Short-eared Dog has been found in scattered sites from Colombia to Bolivia and Ecuador to Brazil. Its presence in Venezuela was suggested by Hershkovitz (1961) but never confirmed. Various studies have suggested the presence of the species throughout the entire Amazonian lowland forest region, as well as Andean foothill forests in Ecuador and Peru up to 2,000 m (Emmons and Feer 1990, 1997; Tirira 1999; A. Plenge pers. comm. 2002).

For the 2004 assessment, museum specimens were re-checked and an extensive survey of field biologists doing long-term research in the species' putative range was carried out, constructing a distributional map based only on specimens of proven origin and incontrovertible field sightings (Leite Pitman and Williams 2004). This map has been refined with subsequent sighting records (M.R.P. Leite Pitman pers. obs.). The northernmost record is in Mitú, Colombia, at 1º15'57"N, 70º13'19"W (Hershkovitz 1961), the southernmost in Bolivia at 14°25'47.9994"S, 63°13' 47.9994"W (R. Wallace pers. obs.), the easternmost record is from the vicinity of Fazenda Amanda, Viseu, Brazil, at 01º52'S, 46º44'W (Pereira 2002), and the westernmost in the Rio Santiago, Peru, at 4º37'S, 77º55'W (Museum of Vertebrate Biology, University of California, Berkeley, collected 1979).

A single specimen [MACN 31.59 held in the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”. (MACN). Colección de Mamíferos] collected on 4 June 1930 is documented as coming from western Pichincha in Ecuador (O.B. Vaccaro pers. comm.). A detailed locality is not provided and it is likely that it is mislabelled; the same collector collected another specimen on 30 July 1930 east of the Andes in Ecuador (specimen also in MACN). However, if the locality is correct, this would be the only record of the species west of the Andes and would mean that the species also previously occurred in the Chocó.

A specimen in the Santa Cruz Natural History Museum labelled as Atelocynus microtis, was genetically analysed and found to be a specimen of Cerdocyon thous (L. Emmons, pers. comm. 2008) which highlights the potential for misidentification between the two species in areas of savannah-forest ecotone in southern Amazonia (where the two species coexist).

Population trend:Decreasing

Population Information

The Short-eared Dog is notoriously rare, and sightings are uncommon across its range. However, this may not always have been the case. The first biologists to study the species found it relatively easy to trap during mammal surveys around Balta, Amazonian Peru, in 1969 (A.L. Gardner and J.L. Patton pers. comm.). Grimwood (1969) reported collecting specimens around the same time in Peru's Manu basin (now Manu National Park), suggesting that the species was also relatively common in that area.

Following these reports, the species went practically unrecorded in the Peruvian Amazon until 1987, despite intensive, long-term field surveys of mammals in the intervening years (Terborgh et al. 1984; Janson and Emmons 1990; Woodman et al. 1991; Pacheco et al. 1993, 1995). Even Louise Emmons, who carried out long-term monitoring and trapping of Ocelots (Leopardus pardalis) and other mammals at the Cocha Cashu Biological Station in Manu, never saw or trapped the Short-eared Dog (L. Emmons pers. comm. 2008). For whatever reason, the species appears to have gone entirely unrecorded from the region between 1970 and 1987.

This local and temporary disappearance is potentially related to transmission of diseases by domestic dogs, commonly brought by local indigenous into protected areas. Two disease surveys carried out in Manu National Park found parvovirus and distemper to be common among domestic dogs, posing a threat to Short-eared Dog populations and other carnivores inside Manu and Alto Purus National Park (Schenck et al. 1997; Leite Pitman, Nieto et al. 2003).

Over the last two decades, it appears that the species population may be recovering in some areas, with increasing numbers of sightings in recent years, but which also certainly reflects a greater number of biologists and tourists in the region and improvements in detection technology such as the use of camera-traps. Between 1987 and 1999, biologists working in the Peruvian department of Madre de Dios, mostly in the vicinity of Cocha Cashu Biological Station, reported 15 Short-eared Dog sightings. Surveys in Cocha Cashu conducted from 2000–2003 resulted in a few brief encounters, while surveys around the Curanja and Purus rivers found tracks in every creek visited (M.R.P. Leite Pitman pers. obs.). From 2003 to date, more than 100 camera-trap pictures of this species have been recorded at Los Amigos Biological Station, also in south-eastern Peru (M.R.P. Leite Pitman pers. obs.). The species has also been recorded by camera traps in northern Peru, Colombia, Ecuador, Bolivia and western and eastern Brazil.

Habitat and Ecology Information

The Short-eared Dog favours undisturbed rainforest in the Amazonian lowlands. The species has been recorded in a wide variety of lowland habitats, including terra firme forest, swamp forest, stands of bamboo, and primary succession along rivers. At Cocha Cashu, sightings and tracks of the species are strongly associated with rivers and creeks, and there are five reliable reports of Short-eared Dogs swimming in rivers. Records are very rare in areas with significant human disturbance, i.e., near towns or in agricultural areas. It is unclear whether the Short-eared Dog is able to utilize habitats outside wet lowland forests. One sighting in Rondonia, Brazil, was in lowland forest bordering savanna (M. Messias pers. comm.). The species has also been recorded up to 2,000 m elevation in montane forest on ridges adjacent to lowlands.

In an ongoing field study initiated in Madre de Dios, Peru in 2000, a female tracked for one year used an area of 8 km² and a dispersing male 30km² in 3 months. Preliminary evidence suggests that male territories probably do not overlap (M.R.P. Leite Pitman pers. obs.).

Threats Information

The major threats to this species are habitat loss (especially due to large-scale conversion currently underway in Amazonia), prey-base depletion from hunting, and diseases. There are no reports of widespread persecution of the species.

Use and Trade Information

Reports of commercial use are scattered and few. In some cases, wild individuals have been captured for pets and occasionally for sale to local people and zoos.

Conservation Actions Information

Although protected on paper in most range countries, this has not yet been backed up by specific conservation action, although the species’ presence was a major factor for conservation efforts at Jamari National Forest, western Brazil (Koester et al. 2008).

The Short-eared Dog is likely to occur in most protected areas that encompass large tracts of undisturbed forest in western Amazonia. During the last decade, its presence has been confirmed in protected areas in Bolivia, Brazil, Ecuador and Peru.

The species is not included in the CITES Appendices.

No animals currently are known to be in formal captive breeding programmes. In the past, individuals have been held in several U.S. zoos (including the Lincoln Park Zoo, the National Zoo, the Brookfield Zoo, the Oklahoma City Zoo, and the San Antonio Zoo), mostly during the 1960s and 1970s (Leite Pitman and Williams 2004).

The biology, pathology, and ecology of the species are little known. Especially lacking is any true estimate of population density and an understanding of the species' habitat requirements. New GPS tracking technology will facilitate studies on density, habitat use and home-range.