- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

Central & North AmericaRed wolf Canis rufus

red wolf - © Art Beyer

Wolf Working Group - The Wolf working group (formally the Wolf specialist group) is an international organisation of experts on wolves. With wolf conservation matters of internal significance, cooperation across the key geographic areas is paramount. The working group plays a key role in this by allowing for the joint planning of conservation programs, exchange of experiences, research and publications and an assembly of knowledgeable personnel across the globe.

Projects- Reintroduction and recovery of endangered red wolves

- Using sterilized placeholders to deter interbreeding between red wolves and coyotes

- Population viability analysis and demographic models of endangered red wolves

- Inbreeding, variation at immune genes, and disease susceptibility in endangered red wolves

English: Red Wolf

German: Rotwolf

Taxonomic Notes

See Chambers et al. (2012) for a brief review of recent literature concerning the status of this species, which they considered a full species, as does this assessment.

Justification

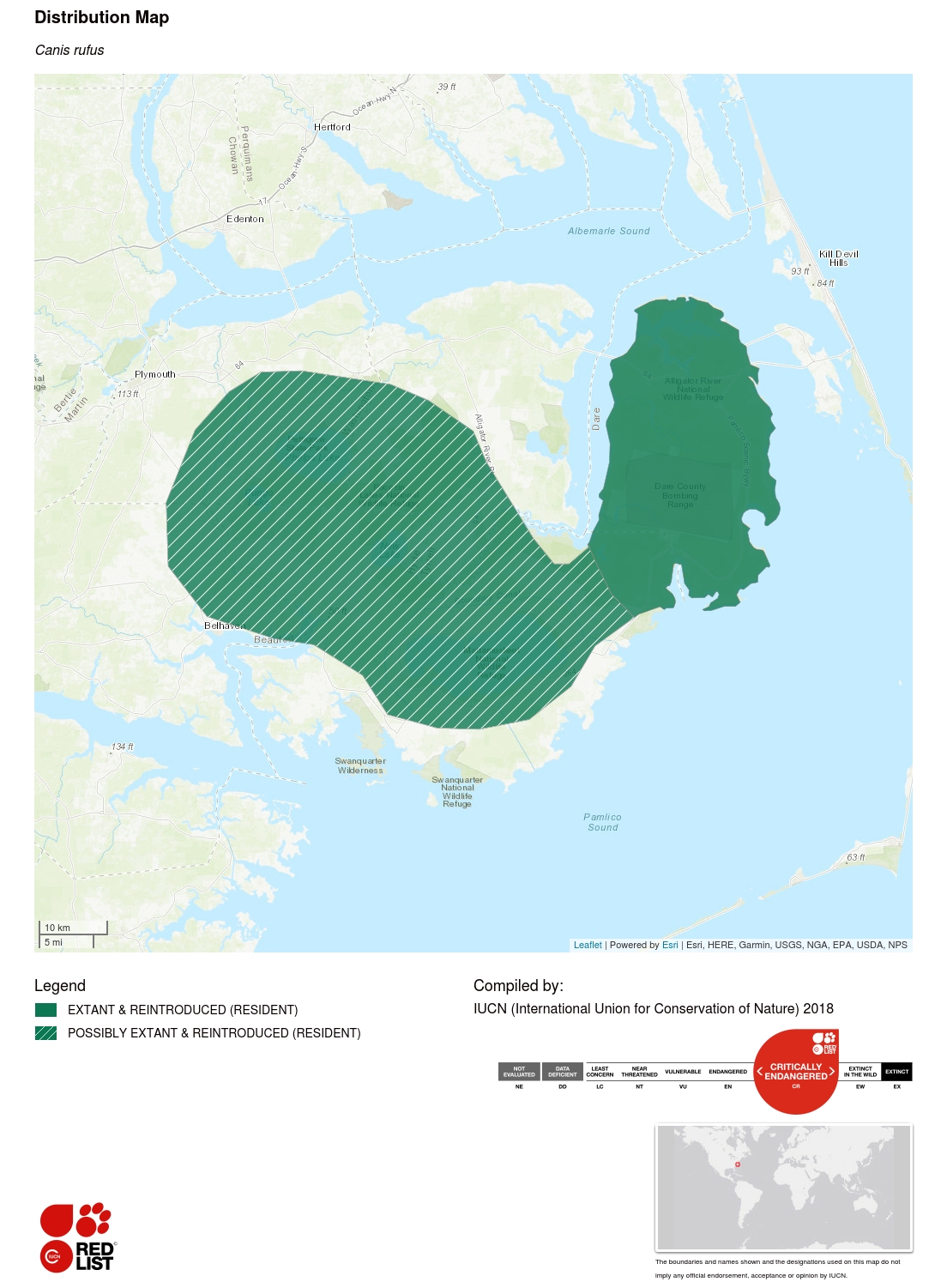

The Red Wolf was Extinct in the Wild by 1980, but was reintroduced by the United States Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) in 1987 into eastern North Carolina. By the early 2000s the total population within the reintroduction area included more than 150 animals. By 2016, the USFWS began restricting the reintroduction effort to federal public land in mainland Dare County, North Carolina (i.e., the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge and Dare County Bombing Range). This ~ 800 km² area can support no more than 20 to 30 wolves. If such a restriction is finalized wolves living outside this area probably will be afforded little or no federal protection or be captured and returned to captivity to bolster the vigour of the captive breeding programme. Hybridization with Coyotes or Red Wolf x Coyote hybrids and landowner intolerance (and subsequent human-caused mortality) are the primary threats to the species' persistence in the wild.

Geographic Range Information

As recently as 1979, the Red Wolf was believed to have a historical distribution limited to the south-eastern United States (Nowak 1979). However, Nowak (1995) described the Red Wolf's historic range as extending northward into central Pennsylvania and later redefined the Red Wolf's range as extending even further north into the north-eastern USA and extreme eastern Canada (Nowak 2002). Recent genetic evidence supports a similar but even greater extension of historic range into Algonquin Provincial Park in southern Ontario, Canada (Chambers et al. 2012). Today the species is largely restricted to federal public lands of mainland Dare County, North Carolina.

Population trend:Decreasing

Population Information

Free-ranging Red Wolves exist only in a reintroduced population in eastern North Carolina, USA. The Red Wolf had been reintroduced to this area in 1987 and within 15 years it had grown to occupy federal, state, and private lands to the west of mainland Dare County. Chronic concerns over Red Wolves hybridizing with Coyotes and Red Wolf/Coyote hybrids and increasing conflict with landowners, prompted the USFWS to consider restricting the Red Wolf restoration effort to federal lands in mainland Dare County in an area that can support no more than 20-30 individuals.

Habitat and Ecology Information

Very little is known about Red Wolf habitat because the species' range was severely reduced by the time scientific investigations began. Given their wide historical distribution, Red Wolves probably utilized a large suite of habitat types at one time. The last naturally occurring population utilized the coastal prairie marshes of south-west Louisiana and south-east Texas (Carley 1975; Shaw 1975). However, many agree that this environment probably does not typify preferred Red Wolf habitat. There is evidence that the species was found in highest numbers in the once extensive bottomland river forests and swamps of the south-east (Paradiso and Nowak 1971, 1972; Riley and McBride 1972). Red Wolves reintroduced into north-eastern North Carolina and their descendants have made extensive use of habitat types ranging from agricultural lands to pocosins. Pocosins are forest/wetland mosaics characterized by an overstory of loblolly and pond pine (Pinus taeda and Pinus serotina, respectively) and an understory of evergreen shrubs (Christensen et al. 1981). This suggests that Red Wolves are habitat generalists and can thrive in most settings where prey populations are adequate and persecution by humans is slight. The findings of Hahn (2002) seem to support this generalization in that low human density, wetland soil type, and distance from roads were the most important predictor of potential wolf habitat in eastern North Carolina.

Threats Information

Hybridization with Coyotes or Red Wolf x Coyote hybrids is the primary threat to the species' persistence in the wild (Kelly et al. 1999). While hybridization with Coyotes was a factor in the Red Wolf's initial demise in the wild, it was not detected as a problem in north-eastern North Carolina until approximately 1992 (Phillips et al. 1995). Indeed, north-eastern North Carolina was determined to be ideal for Red Wolf reintroductions because of a purported absence of Coyotes (Parker 1986). However, during the 1990s, the Coyote population apparently became well established in the area (P. Sumner pers. comm.; USFWS, unpubl.). From the start of the reintroduction project in 1987 through to about 2005, the Red Wolf population grew to more than 150 animals. Intensive management was useful at minimizing the extent of hybridization with Coyotes and Coyote/Red Wolf hybrids (Gese and Terletzky 2015, Gese et al. 2015). However, by about 2012, the reintroduction project had become notably characterized by significant conflict with landowners (primarily over Coyote management and general frustration with the USFWS’s implementation of the Red Wolf recovery programme) which led to a substantial increase in the illegal killing of Red Wolves.

Use and Trade Information

Conservation Actions Information

The species is not included on the CITES Appendices. The Red Wolf is listed as endangered under the U.S. Endangered Species Act (ESA) (United States Public Law No. 93-205; United States Code Title 16 Section 1531 et seq.). The reintroduced animals and their progeny in north-eastern North Carolina are considered members of an experimental non-essential population. This designation was promulgated under Section 10(j) of the ESA and permits the USFWS to manage the population and promote recovery in a manner that is respectful of the needs and concerns of local citizens (Parker and Phillips 1991). Hunting of Red Wolves is prohibited by the ESA. To date, federal protection of the Red Wolf has been adequate to successfully reintroduce and promote recovery of the species in North Carolina.

A very active recovery programme for the Red Wolf has been in existence since the mid-1970s (USFWS 1990; Phillips et al. 2003), with some measures from as early as the mid-1960s (USFWS, unpubl.). By 1976, a captive breeding programme was established using 17 animals captured in Texas and Louisiana (Carley 1975; USFWS 1990). Of these, 14 became the founders of the current captive breeding programme. In 1977, the first pups were born in the captive programme, and by 1985, the captive population had grown to 65 individuals in six zoological facilities (Parker 1986). As of 2017 there were approximately 175 Red Wolves in captivity at 43 facilities throughout the United States and Canada (USFWS, unpubl.). The purpose of the captive population is to safeguard the genetic integrity of the species and to provide animals for reintroduction.

With the species reasonably secure in captivity, the USFWS began reintroducing Red Wolves at the Alligator River National Wildlife Refuge in north-eastern North Carolina in 1987. As of September 2002, 102 animals have been released with a minimum of 281 descendants produced in the wild since 1987. By 2005, the population had grown to include more than 150 wolves distributed across nearly 6,000 km² of private land (~ 70%) and public land (~30%). The public land included three national wildlife refuges (Alligator River NWR, Pocosin Lakes NWR, and Mattamuskeet NWR) which provided important protection to the wolves. Notably, the USFWS also estimated that over a dozen hybrid canids were also present in north-eastern North Carolina.

However, by about 2012 the reintroduction project had become mired in significant conflict with landowners (primarily over Coyote management and general frustration with the USFWS’s implementation of the Red Wolf recovery programme) that led to a substantial increase in illegal killing of wolves. In response to these characterizations, starting in 2016 the USWFS began taking steps to significantly change the direction of the Red Wolf recovery programme. By 2016 and 2017, changes being cemented into action included: 1) improving the foundation of the captive breeding programme to ensure that the species did not go extinct; 2) restricting free-ranging Red Wolves to about 800 km² of federal lands in mainland Dare County, North Carolina, an area that can support no more than 20 or 30 such animals; 3) returning all Red Wolves found elsewhere in north-eastern North Carolina to captivity to assist with #1 or providing such animals with little or no federal protection; and 4) assessing potential sites throughout the south-eastern United States for future reintroduction projects. Absent successful reintroductions that result in the restoration of several hundred red wolves (at one or a few sites), recovery of the species under the U.S. Endangered Species Act will not be possible.

During 1991, a second reintroduction project was initiated at the Great Smoky Mountains National Park, Tennessee (Lucash et al. 1999). Thirty-seven Red Wolves were released from 1992 to 1998. Of these, 26 either died or were recaptured after straying onto private lands outside the Park (Henry 1998). Moreover, only five of the 32 pups known to have been born in the wild survived, but were removed from the wild during their first year (USFWS, unpubl.). Biologists suspect that disease, predation, malnutrition, and parasites contributed to the high rate of pup mortality (USFWS, unpubl.). Primarily because of the poor survival of wild-born offspring, the USFWS terminated the Tennessee restoration effort in 1998 (Henry 1998).