- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

Europe & North/Central AsiaRed fox Vulpes vulpes

red fox - © Patty Hoyt

Projects- Climate change and the decline of an alpine-adapted carnivore—the Sierra Nevada red fox (Vulpes vulpes necator): upward range shifts by competitors or changing prey communities?

- Testing habitat models for the endemic Sacramento Valley red fox (Vulpes vulpes patwin)

- Ecology of native montane red foxes (Vulpes vulpes ssp.) of the southern Cascades and Great Basin Mountain Ranges

- Canid conservation in the Gobi-Steppe ecosystem of Mongolia

- Project Coyote - Ranching with Wildlife

- Ecology and Conservation of the Cascade Red Fox

English: Red Fox, Cross Fox, Silver Fox

French: Renard roux

Spanish; Castilian: Zorro, Zorro Rojo

Albanian: Dhelpra

Croatian: Lisica

Dutch; Flemish: Vos

German: Rotfuchs

Italian: Volpe Comune, Volpe Rossa

Maltese: Volpi

Polish: Lis

Portuguese: Raposa

Romanian: Vulpe

Russian: K?????? ????

Serbian: Lisica

Turkish: Tilki

Taxonomic Notes

A recent extensive global phylogeny of Red Foxes that included ~1,000 samples from across the species’ range found that Red Foxes originated in the Middle East, then radiated out, and that Red Foxes in North America are genetically distinct and probably merit recognition as a distinct species (Vulpes fulva) (Statham et al. 2014).

Justification

The Red Fox has the widest geographical range of any member of the order Carnivora, being distributed widely across the entire northern hemisphere, and has been introduced elsewhere. Red Foxes are adaptable and opportunistic omnivores and are capable of successfully occupying urban areas. In many habitats, foxes appear to be closely associated with people, even thriving in intensive agricultural areas.

Geographic Range Information

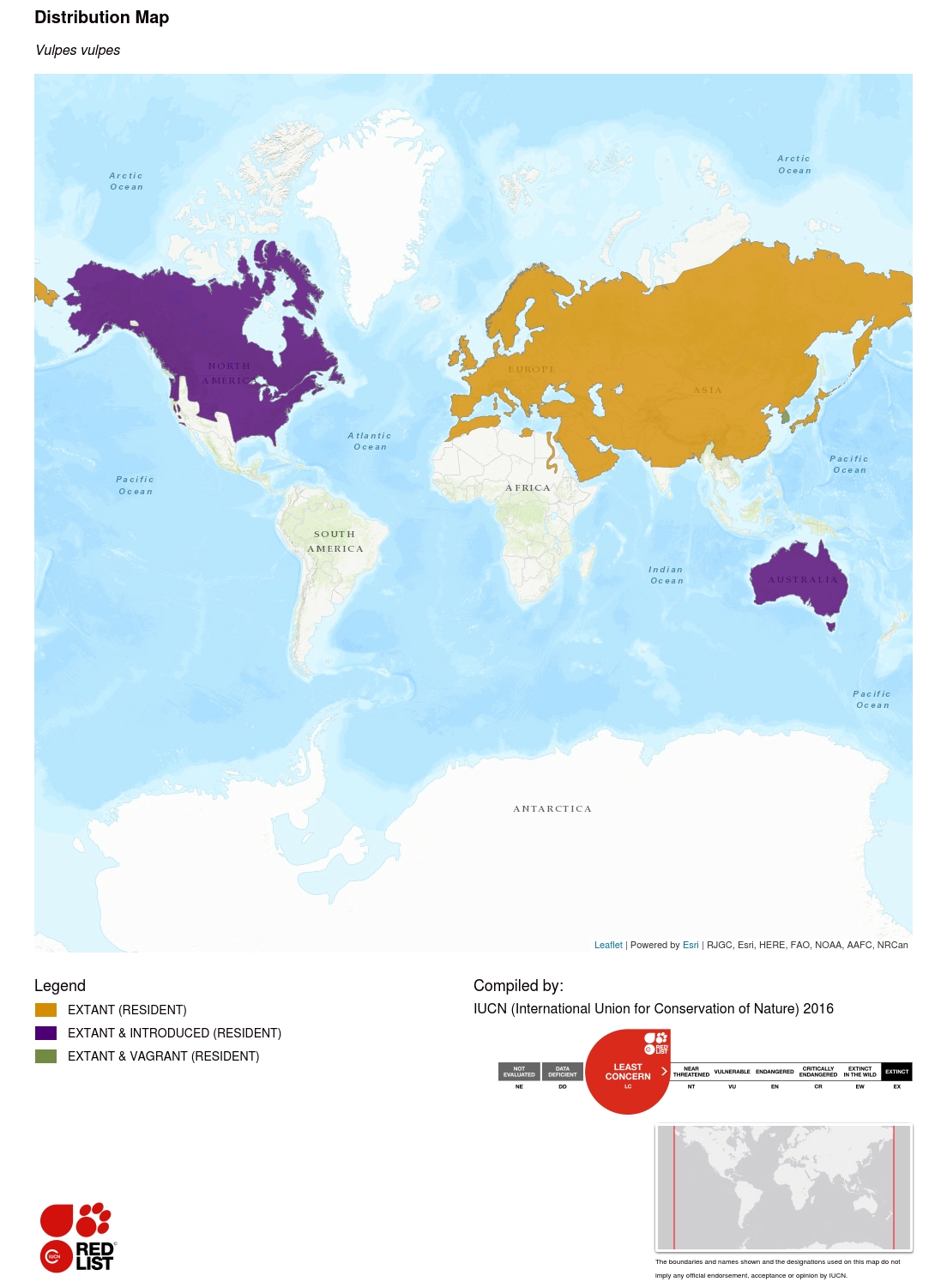

The Red Fox has the widest geographical range of any member of the order Carnivora (covering nearly 70 million km²) being distributed across the entire northern hemisphere from the Arctic Circle to southern North America, Europe, North Africa, the Asiatic steppes, India, and Japan. Not found in Iceland, the Arctic islands, or some parts of Siberia. Red Foxes are generally considered extinct in the Republic of Korea where there have been several mammal surveys in recent years (including the DMZ) that have not shown any evidence of foxes.

The European subspecies was introduced into the eastern United States (where they were relatively scarce and the Gray Fox Urocyon cinereoargenteus common) and Canada in the 17th century for fox hunting; however, there appears to be limited evidence for any meaningful mixing of introduced European foxes and those in North America (i.e., no Eurasian haplotypes found in foxes sampled; Statham et al. 2012). The species was also introduced to Australia in the 1800s, and to Tasmania in the late 1990s (although there is evidence that an eradication campaign for Red Foxes on Tasmania has proved effective; see Caley et al. 2015). Elsewhere introduced to the Falkland Islands (Malvinas) and to the Isle of Man (UK), although they never properly established on the Isle of Man (Reynolds and Short 2003) and may subsequently have disappeared.

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

Red Fox density is highly variable. In the United Kingdom, density varies between one fox/40 km² in Scotland and 1.17/km² in Wales, but can be as high as 30 foxes/km² in some urban areas where food is superabundant (Harris 1977, Macdonald and Newdick 1982, Harris and Rayner 1986). Social group density is one family per km² in farmland, but may vary between 0.2-5 families/km² in the suburbs (Macdonald 1981). Fox density in mountainous rural areas of Switzerland is three foxes/km² (Meia 1994). Murdoch (2009) recorded 0.17 foxes/km² in the grassland/semi desert steppe of Mongolia. In northern boreal forests and Arctic tundra, they occur at densities of 0.1 foxes/km², and in southern Ontario, Canada at 1 fox/km² (Voigt 1987). The average social group density in the Swiss mountains is 0.37 families/km² (Weber et al. 1999).

The pre-breeding British fox population has been estimated at ~240,000 individuals (Harris et al. 1995). Mean number of foxes killed per unit area by gamekeepers has increased steadily since the early 1960s in Britain, but it is not clear to what extent this reflects an increase in fox abundance. Although an increase in fox numbers following successful rabies control by vaccination was widely reported in Europe (e.g., fox bag in Germany has risen from 250,000 in 1982–1983 to 600,000 in 2000–2001), no direct measures of population density have been taken.

Habitat and Ecology Information

Red Foxes have been recorded in habitats as diverse as tundra, desert (though not extreme deserts) and forest, as well as in city centres (including London, Paris, Stockholm, etc.). Natural habitat is dry, mixed landscape, with abundant "edge" of scrub and woodland. They are also abundant on moorlands, mountains (even above the treeline, known to cross alpine passes), sand dunes and farmland from sea level to 4,500 m. In the United Kingdom, they generally prefer mosaic patchworks of scrub, woodland and farmland. Red Foxes flourish particularly well in urban areas. They are most common in residential suburbs consisting of privately owned, low-density housing and are less common where industry, commerce or council rented housing predominates (Harris and Smith 1987). In many habitats, foxes appear to be closely associated with people, even thriving in intensive agricultural areas.

Threats Information

Threats to this species are highly localized and include habitat degradation, loss, and fragmentation, and exploitation, and direct and indirect persecution. For example, a regional red list assessment in Mongolia (Clark and Munkhbat 2006) classified the species as Near Threatened mainly due to overhunting, while in South Korea, Red Foxes have experienced declines due to habitat loss and poaching and is generally considered extinct (Yu et al. 2012). However, their general versatility and eclectic diet are likely to ensure their persistence despite changes in landscape and prey base. Culling may be able to reduce numbers well below carrying capacity in large regions (Heydon and Reynolds 2000), but no known situations exist where this currently threatens species persistence on any geographical scale. Red Foxes have caused considerable damage where they have been introduced; their impacts on Australian fauna has been particularly well documented; control takes place by setting baits impregnated with 1080 (sodium fluoroacetate).

Use and Trade Information

The number of foxes raised for fur (although much reduced since the 1900s) exceeds that of any other species, except possibly American Mink (Neovison vison) (Obbard 1987). Types farmed are particularly colour variants ("white", "silver" and "cross") that are rare in the wild. Worldwide trade in ranched Red Fox pelts (mainly "silver" pelts from Finland) was 700,000 in 1988–1989 (excluding internal consumption in the USSR). Active fur trade in Britain in 1970s was negligible.

Conservation Actions Information

Legislation

Not listed in CITES Appendices at species level. However, the subspecies griffithi, montana and pusilla (=leucopus) are listed on CITES – Appendix III (India).

Widely regarded as a pest and unprotected. Most countries and/or states where trapping or hunting occurs have regulated closed versus open seasons and restrictions on methods of capture. In the European Union, Canada, and the Russian Federation, trapping methods are regulated under an agreement on international trapping standards between these countries, which was signed in 1997. Other countries are signatories to ISO/DIS 10990-5.2 animal (mammal) traps, which specifies standards for trap testing.

In Europe and North America, hunting traditions and/or legislation impose closed seasons on fox hunting. In the United Kingdom and a few other European countries, derogation from these provisions allows breeding season culling for pest-control purposes. Here, traditional hunting ethics encouraging restrained "use" may be at odds with harder hitting pest-control ambitions. This apparent conflict between different interest groups is particularly evident in the UK, where fox control patterns are highly regionally variable (Macdonald et al. 2003). In some regions, principal lowland areas where classical mounted hunting operates, limited economic analyses suggest that the principal motive for these communal fox hunts is as a sport – the number killed is small compared with the cost of the hunting. In these regions, most anthropogenic mortality is by individual farmers shooting foxes. The mounted communal hunts do exhibit restraint – hunting takes place for a limited season, and for a prescribed number of days per week. Elsewhere, in upland regions, communal hunting by foot with guns and dogs may make economic sense, depending on the number of lambs lost to foxes (data on this is poor), and also on the current value of lost lambs. This type of fox hunting may also be perceived as a sport by its participants.

Presence in protected areas

Present in most temperate-subarctic conservation areas.

Presence in captivity

In addition to fur farms, Red Foxes are widely kept in small wildlife parks and zoos, but there appears to be no systematic data on their breeding success. Being extremely shy they are often poor exhibits.