- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

South AmericaPampas Fox Lycalopex gymnocercus

pampas fox - © Marcelo Dolsan

Amazonian Canids Working Group - Karen DeMatteo and Fernanda Michalski are the coordinators of the Amazonian Canids Working Group. This working group is focused on four species: the short-eared dog, crab-eating fox, bush dog, and South American foxes. Amazonian canids are similar to many carnivores worldwide whose long-term survival is threatened by a variety of direct and indirect threats, including habitat loss, expansion of hydroelectric dams, illegal hunting of prey, and diseases from domestic dogs.

Projects- Impact of pampas foxes (Pseudalopex gymnocercus) on livestock in the Argentine Espinal: evaluation of conflict mitigation measures

- Camera trapping as a method to estimate population abundance of mammals in temperate grasslands of northern Uruguay: density calculation models applied to carnivore species

Synonym: Pseudalopex gymnocercus

English: Pampas Fox, Azara's Fox, Azara's Zorro, Azara’s Fox

French:Renard d'Azara

Spanish; Castilian:Zorro Pampa, Zorro Pampeano, Zorro de Azara, Zorro de Campo, Zorro de Patas Amarillas, Zorro del País

German: Pampasfuchs

Italian: Volpe Azara, Volpe Grigia Delle Pampas

Portuguese: Cachorro do Campo, Graxaim do Campo, Rasposa do Mato

Taxonomic Notes

Several recent molecular studies have provided support for a monophyletic assemblage of South American endemic canids (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005, Perini et al. 2010), with Chrysocyon and Speothos forming a sister-clade to the monophyletic South American foxes and Atelocynus. On the basis of morphology, Zunino et al. (1995) reviewed previous work and also supported clustering species within the two previous paraphyletic genera (Pseudalopex, Lycalopex) into a single monophyletic genus. They further argued that Lycalopex had priority over Pseudalopex, subsequently also supported by Zrzavý et al. (2004: 324). The only outstanding question would have been whether Dusicyon would have been a more appropriate name, since Perini et al. (2010) reported a close relationship between L. culpaeus and Dusicyon. However, we now know that Dusicyon is far outside this clade (Slater et al. 2009, Austin et al. 2013). Based on this evidence, the genus Lycalopex is used over Pseudalopex for all South American foxes, following Wozencraft's (2005) earlier treatment.

Two morphometric studies (Zunino et al. 2005, Prevosti et al. 2013) have suggested that Lycalopex gymnocercus and the Chilla (L. griseus) belong to the same species, with clinal differences in size. However, as Prevosti et al. (2013) note, most genetic studies have not recovered the two species as a monophyletic group (although see Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005). Given this uncertainty, and since both species are in any event assessed as Least Concern, we provisionally continue to recognize Pampas Fox and Chilla as two distinct species, pending further taxonomic investigations.

Justification

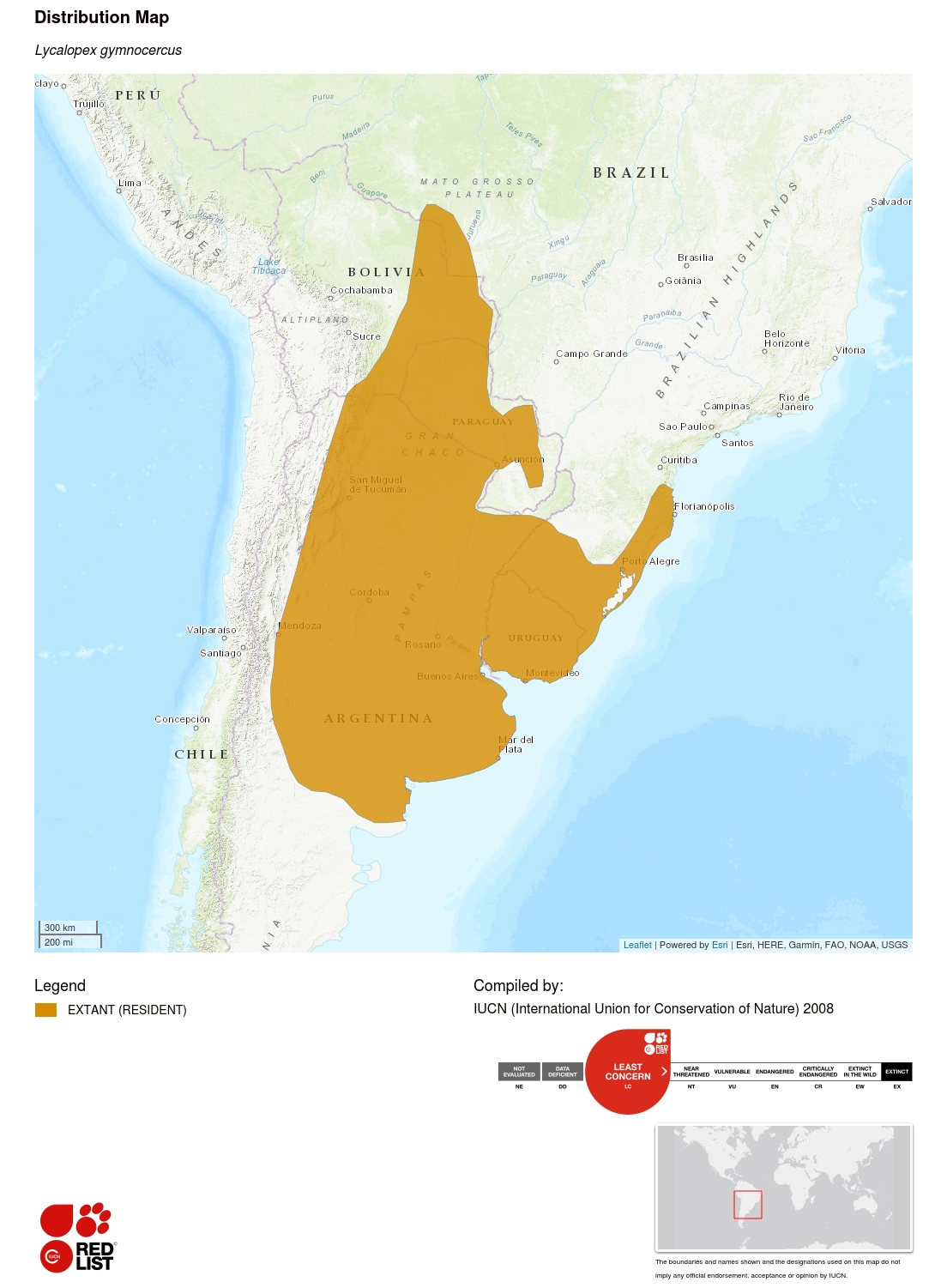

The Pampas Fox inhabits the Southern Cone of South America, where it is either abundant or common in most areas where the species has been studied. The species seems to be tolerant of human disturbance, being common in rural areas, where introduced exotic mammals could form the bulk of its food intake. There is no reason to believe the species is currently declining and the species is not considered threatened at present.

Geographic Range Information

The Pampas Fox inhabits the Southern Cone of South America, occupying chiefly the Chaco, Argentine Monte, Argentine Espinal and Pampas eco-regions (Lucherini et al. 2004, Lucherini and Luengos Vidal 2008). It ranges from eastern Bolivia, western Paraguay and east of Salta, Catamarca, San Juan, La Rioja and Mendoza provinces in Argentina, to the Atlantic coast; and from south-eastern Brazil to the Río Negro Province, Argentina, in the south. Information on the limits of its distribution and the extent to which it overlaps with Chilla (Lycalopex griseus) is uncertain.

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

Little quantitative data are available on the abundance of Pampas Fox populations. Population densities of 1.8 individuals/km² and 1.1-1.5 individuals/km² were estimated for the Bolivian Chaco (Ayala and Noss 2000) and a protected area of central Argentina (Luengos Vidal et al. 2012), respectively. Although no long-term population monitoring has been carried out, populations generally are considered stable.

In the coastal area of central Argentina, a study based on scent-stations found that Pampas Fox signs were more frequent than Molina's Hog-nosed Skunk (Conepatus chinga) and Grison (Galictis cuja) (García and Kittlein 2005). Similarly, the frequency of observation of Pampas Fox was higher than that of Molina's Hog-nosed Skunk, Grison, and Geoffroy's Cat (Leopardus geoffroyi) both in a Sierra grassland area and in a cropland area of Buenos Aires Province (Luengos et al. 2005). Recent camera trapping data indicate that it is the most common carnivore in an area of 27,300 km² of the Argentine Espinal (Caruso 2015). In areas where the Pampas Fox is sympatric with the Crab-eating Fox (Cerdocyon thous), the former would be more abundant in open habitats, while the latter would more frequently inhabit woodland areas (Vieira and Port 2007, Di Bitetti et al. 2009, Faria-Corrêa et al. 2009).

The Pampas Fox seems to be tolerant of human disturbance, being common in rural areas, where introduced exotic mammals, such as the European hare (Lepus europaeus), could form the bulk of its food intake (Crespo 1971, Farias and Kittlein 2008, D. Birochio and M. Lucherini pers. obs.).

Habitat and Ecology Information

The Pampas Fox is a typical inhabitant of the Southern Cone Pampas grasslands. It prefers open habitats and tall grass plains and sub-humid to dry habitats, but is also common in ridges, dry scrub lands, coastal sand dunes, open woodlands, and in modified habitats, such as grazed pastures and croplands (Brooks 1992, Redford and Eisenberg 1992, Lucherini and Luengos Vidal 2008). In the driest habitats in the southerly and easterly parts of its range, the species is replaced by the Chilla. Where its range overlaps with that of the Crab-eating Fox, the Pampas Fox would select more open areas. Apparently, the Pampas Fox has been able to adapt to the alterations caused by extensive cattle breeding and agricultural activities to its natural habitats.

In a coastal area of northern Patagonia, the Pampas Fox used all available habitats (García and Kittlein 2005). Radio-collared Pampas Foxes preferred the most preserved habitats both in a natural grassland area and a cropland area of the Argentine Pampas. However, this preference was stronger in the most modified area (Luengos Vidal 2009).

Threats Information

The implementation of control measures (promoted by ranchers) by official organizations, coupled with the use of non-selective methods of capture such as poison, represent the main threats for the Pampas Fox. Fox control by government agencies involves the use of bounty systems without any serious studies on population abundance or the real damage that this species may cause. In rural areas, direct persecution in retaliation for or prevention of predation on lambs is also common, even where hunting is officially illegal and despite the true economic impact of predation being unquantified (Lucherini and Luengos Vidal 2008, M. Lucherini pers. obs. 2015).

Most of the species' range has suffered massive habitat alteration. For instance, the Pampas, which represents a large proportion of the species' distribution range, has been affected by extensive cattle breeding and agriculture. Approximately 0.1% of the original 500,000 km² range remains unaffected. However, due to the species' adaptability, the Pampas Fox seems able to withstand the loss and degradation of its natural habitat, as well as hunting pressure. Since no studies are available on its population dynamics in rural ecosystems, caution is required, since the sum of these threats may eventually promote the depletion of fox populations. Hunting pressure has resulted in diminished populations in the provinces of Tucumán (Barquez et al. 1991) and Salta (Cajal 1986) of north-western Argentina.

Use and Trade Information

Rural residents have traditionally hunted the Pampas Fox for its fur, and this activity has been an important source of income for them. From 1975 to 1985, Lycalopex fox skins (mostly belonging to L. gymnocercus; García Fernández 1991) were among the most numerous to be exported legally from Argentina (Chebez 1994). Further, some authors have pointed out that Argentine exports corresponding to the Chilla historically included other species, such as the Crab-eating Fox and the Pampas Fox (Ojeda and Mares 1982, García Fernandez 1991). However, exports have declined from the levels of the early and mid-1980s mainly due to a decline in demand (Novaro and Funes 1994). Today, the trade in Pampas Fox is banned, and no statistical information on the fur harvest is available.

Conservation Actions Information

Legislation

Included in CITES – Appendix II.

In Argentina, it was declared not threatened in 1983 and its trade was prohibited in 1987. However, this species continues to be hunted and demand for its fur exists. In Uruguay, all foxes are protected by law, and the only legal exception is the government's so-called "control hunting permission", which does not allow the taking of animals for the fur trade. The situation is very similar in Paraguay.

Presence in protected areas

Although it occurs in a number of protected areas in Argentina, the proportion of its range under protection is low in this country. In Uruguay, the Pampas Fox has been reported in many protected areas; however, illegal hunting of foxes still occurs within these areas (Y. Hernandez pers. comm. 2015).

Presence in captivity

In Argentina, the Pampas Fox has been successfully bred in captivity and presently is the best represented carnivore species in captivity in the country (Aprile 1999).

Gaps in knowledge

Many aspects of the species' ecology remain unknown. Studies on population dynamics in agricultural land, impact and sustainability of hunting, effect of predation on livestock and game species are needed, particularly for an appropriate management of wild populations. In addition, as noted under Taxonomy, the status of this species with respect to the Chilla requires further investigation.