- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

Europe & North/Central AsiaArctic fox Vulpes lagopus

Arctic fox - © Love Dalén

Relevant Links- Flickr: Wild Canids of the World

- 2014 IUCN Red List Assessment - Arctic Fox

- European Commission - Boosting Arctic Fox Numbers

English: Arctic Fox, Polar Fox

French: Isatis, Renard Polaire, Reynard Polaire

Spanish; Castilian: Zorro Ártico

German: Polarfuchs

Russian: Ïåñåö

Taxonomic Notes

Often included in the genus Alopex, current evidence suggests that inclusion in Vulpes (sensu Wozencraft 2005) is warranted as Vulpes is otherwise paraphyletic with respect to Alopex. Nuclear and matrilineal (mitochondrial) DNA unambiguously support the inclusion of Alopex lagopus in Vulpes (Geffen et al. 1992, Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005, Perini et al. 2010).

Justification

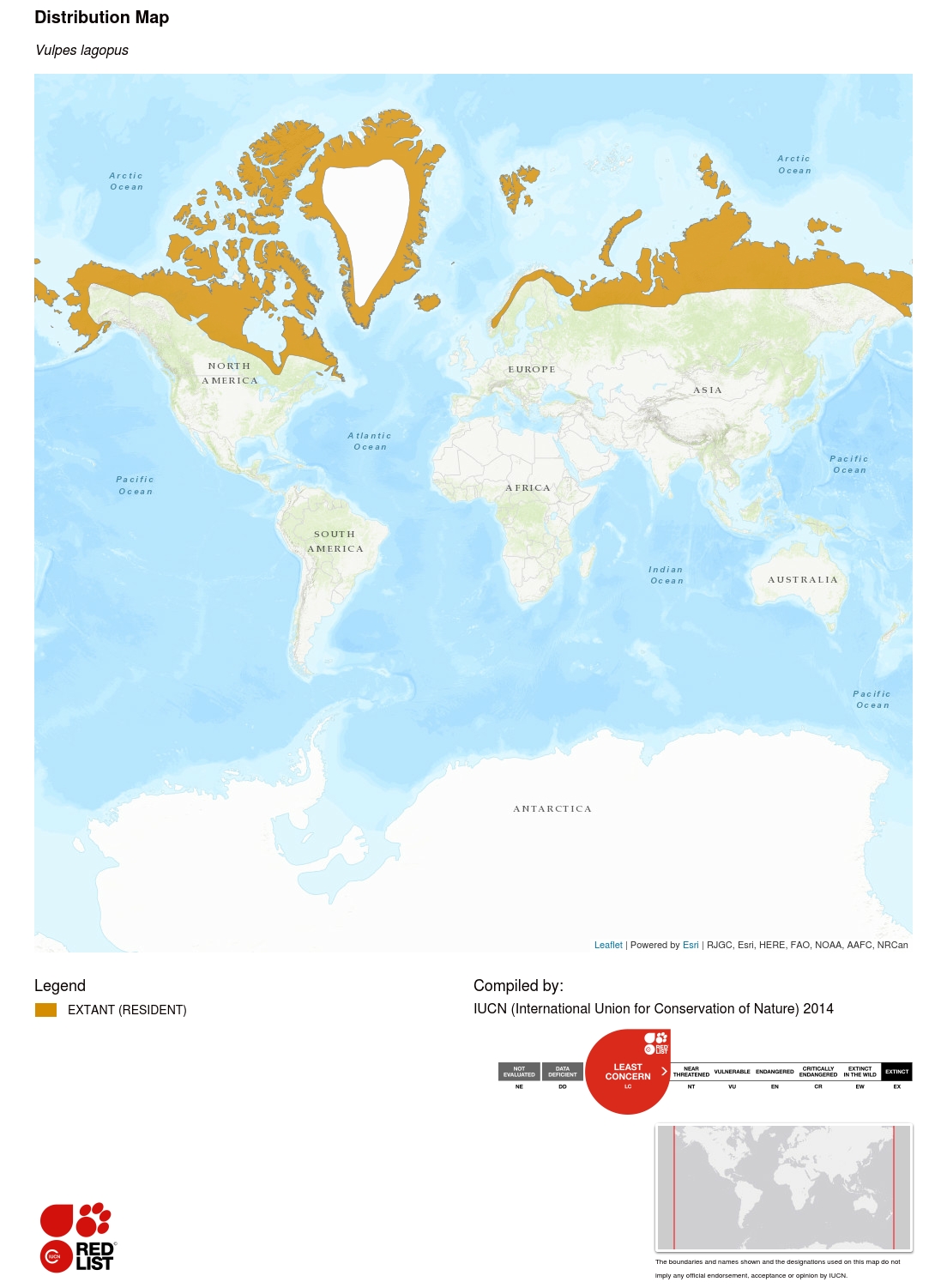

The Arctic Fox has a circumpolar distribution in all Arctic tundra habitats, with a global population in the order of several hundred thousand animals. Most populations fluctuate widely in numbers between years in response to varying lemming numbers, but in most areas population status is believed to be good and there is no reason to believe that the species currently qualifies for listing as threatened under any of the criteria.

Geographic Range Information

The Arctic Fox has a circumpolar distribution in all Arctic tundra habitats. It breeds north of and above the tree line on the Arctic tundra in North America and Eurasia and on the alpine tundra in Fennoscandia, ranging from northern Greenland at 88°N to the southern tip of Hudson Bay, Canada, 53°N. The southern edge of the species' distribution range may have moved somewhat north during the 20th century resulting in a smaller total range (Hersteinsson and Macdonald 1992). The species inhabits most Arctic islands and many islands in the Bering Sea. The Arctic Fox was also introduced to previously isolated islands in the Aleutian chain at the end of the 19th century by the fur industry (Bailey 1992), where they are now often being eliminated by bird conservation efforts (Walton et al. 2013). The Arctic Fox has also been observed on the sea ice up to the North Pole. They may occur up to 3,000 m asl in elevation.

During the last glaciation, the Arctic Fox had a distribution along the ice edge, and Arctic Fox remains have been found in a number of Pleistocene deposits over most of Europe and large parts of Siberia (Dalén et al. 2007).

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

The world population of Arctic Foxes is in the order of several hundred thousand animals. Most populations fluctuate widely in numbers between years in response to varying lemming numbers. In most areas, however, population status is believed to be good. The species is common in the tundra areas of Russia, Canada, coastal Alaska, Greenland and Iceland. Exceptions are Fennoscandia, islands in the Bering Sea (Mednyi Island, Russia; Pribilof Islands, Alaska, e.g., St Paul), where populations are at critically low levels and appear to be declining further. On some Aleutian Islands, Alaska, non-native Arctic Foxes are being eradicated in the course of bird conservation efforts (Walton et al. 2013). Vagrant Arctic Foxes are common over the northern sea-ice where can move several thousands of kilometres following Polar Bears Ursus maritimus as scavengers (Tarroux et al. 2010).

Habitat and Ecology Information

Inhabits Arctic and alpine tundra on the continents of Eurasia, North America and the Canadian archipelago, Siberian islands, Greenland, inland Iceland and Svalbard, and Sub-Arctic maritime habitat in the Aleutian island chain, Bering Sea Islands, Commander Islands and coastal Iceland.

The Arctic Fox is an opportunistic predator and scavenger but in most inland areas, the species is heavily dependent on fluctuating rodent populations. The species' main prey items include lemmings, both Lemmus spp. and Dicrostonyx spp. (Macpherson 1969, Angerbjörn et al. 1999). In Fennoscandia, Lemmus lemmus was the main prey in summer (85% frequency of occurrence in faeces) followed by birds (Passeriformes, Galliformes and Caridriiformes, 34%) and reindeer (Rangifer tarandus) (21%; Elmhagen et al. 2000). In winter, ptarmigan and grouse (Lagopus spp.) are common prey in addition to rodents and reindeer (Kaikusalo and Angerbjörn 1995). Changes in fox populations have been observed to follow those of their main prey in three- to five-year cycles (Macpherson 1969, Angerbjörn et al. 1999, 2013) with up to 20 cubs produced by a single female (Tannerfeldt and Angerbjörn 1998).

Foxes living near ice-free coasts have access to both inland prey and sea birds, seal carcasses, fish and invertebrates connected to the marine environment, leading to relatively stable food availability and a more generalist strategy (Hersteinsson and Macdonald 1996). In late winter and summer, foxes found in coastal Iceland feed on seabirds (Uria aalge, U. lomvia), seal carcasses and marine invertebrates. Inland foxes rely more on ptarmigan in winter, and migrant birds, such as geese and waders, in summer (Hersteinsson and Macdonald 1996). In certain areas, foxes rely on colonies of Arctic geese, which can dominate their diet locally (Samelius and Lee 1998). Some populations switch between lemmings, migratory birds and marine resources depending on intra- and interannual variations in prey availability. The Arctic Fox depends also on remains of carrion left by larger predators, e.g. Polar Bear, Grey Wolf Canis lupus, and Wolverine Gulo gulo. It is itself a victim of predation, mainly from Red Fox, Wolverine, Golden Eagle, and humans.

Threats Information

Hunting for fur has long been a major mortality factor for the Arctic Fox. With the decline of the fur hunting industry, the threat of over-exploitation is lowered for most Arctic Fox populations. They may also be subject to direct persecution (as on St. Paul Island). Misinformation as to the origin of Arctic Foxes on the Pribilofs continues to foster negative attitudes and the long-term persistence of this endemic subspecies is in jeopardy. In areas connected to marine ecosystems, Arctic Foxes may also be affected by indirect threats, such as diseases and the effects of persistent organic pollutants (Sonne et al. 2008); indeed, an emerging threat in Fennoscandia is the impact of sarcoptic mange on populations (Mörner 1992). In some areas, gene swamping by farm-bred blue foxes (see Conservation) may threaten native populations (Norén et al. 2009).

Use and Trade Information

The Arctic Fox remains the single most important terrestrial game species in the Arctic. Indigenous peoples have always utilized its exceptional fur, and with the advent of the fur industry, the Arctic Fox quickly became an important source of income. Today, leg-hold traps and shooting are the main hunting methods. Because of their large reproductive capacity, Arctic Foxes can maintain population levels under high hunting pressure. In some areas, up to 50% of the total population has been harvested on a sustainable basis (Nasimovic and Isakov 1985). However, this does not allow for hunting during population lows, as shown by the situation in Fennoscandia. The Arctic Fox has nevertheless survived high fur prices better than most other Arctic mammals. Hunting has declined considerably in the last decades, as a result of low fur prices and alternative sources of income. In the Yukon, for example, the total value of all fur production decreased from $1.3 million in 1988 to less than $300,000 after 2000.

Conservation Actions Information

The species is not included in the CITES Appendices.

In most of its range, the Arctic Fox is not protected. However, the species and its dens have had total legal protection in Sweden since 1928, in mainland Norway since 1930, and in Finland since 1940. In Europe, the Arctic Fox is a priority species under the Actions by the Community relating to the Environment (ACE). It is therefore to be given full protection. On St. Paul Island the declining Arctic Fox population currently has no legal protection (Walton et al. 2013). In Norway (Svalbard), Greenland, Canada, Russia, and Alaska, trapping is limited to licensed trappers operating in a defined trapping season. The enforcement of these laws appears to be uniformly good. In Iceland, bounty hunting takes place over most of the country outside nature reserves.

For occurrence in protected areas, good information is available only for Sweden and Finland. For Iceland, Arctic Foxes could potentially appear in most protected areas.

An action plan has been developed for Arctic Foxes in Sweden (Elmhagen 2008) and status reports have been published for Norway (Ulvund et al. 2013) and Finland (Kaikusalo et al. 2000). In Sweden, Norway and Finland, a conservation project led to significant increases in the population (Angerbjörn et al. 2013).

The Arctic Fox occurs widely in captivity on fur farms and has been bred for fur production for over 70 years. The present captive population originates from a number of wild populations and has been bred for characteristics different from those found in the wild, including large size. Escaped "blue" foxes may already be a problem in Fennoscandia (and to a lesser extent in Iceland) due to gene swamping (Norén et al. 2009). In Norway, foxes bred in captivity have successfully been released into the wild (Landa et al. 2014).

The following gaps still exist in knowledge of the Arctic Fox:

1) Little is known concerning the impact of diseases on fox populations, e.g. sarcoptic mange and Echinococcus multilocularis. Allied to this is our lack of knowledge of the epidemiology of Arctic rabies.

2) Considering the northward spread of the Red Fox in certain areas, studies are necessary to determine the effects of competition between Red Foxes and Arctic Foxes on various population parameters and Arctic Fox life-history patterns.

3) The non-recovery of the Fennoscandian population is a cause for concern, and requires specific attention, especially in terms of disease and genetics.