- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

South AmericaCrab-eating fox Cerdocyon thous

crab-eating fox - © Adriano Gambarini

Amazonian Canids Working Group - Karen DeMatteo and Fernanda Michalski are the coordinators of the Amazonian Canids Working Group. This working group is focused on four species: the short-eared dog, crab-eating fox, bush dog, and South American foxes. Amazonian canids are similar to many carnivores worldwide whose long-term survival is threatened by a variety of direct and indirect threats, including habitat loss, expansion of hydroelectric dams, illegal hunting of prey, and diseases from domestic dogs.

Projects- Programa de conservação mamíferos do cerrado

- Population ecology of foxes in Mirador State Park, Brazil

- Investigation of neotropical helminthiasis and other parasites in the biotope of wild animals of the Misionera Forest, as potential foci of zoonoses

- Effect of climate change on carnivores in the Amazon

- Camera trapping as a method to estimate population abundance of mammals in temperate grasslands of northern Uruguay: density calculation models applied to carnivore species

English: Crab-eating Fox, Common Zorro, Crab-eating Zorro, Savannah Fox

French: Chien des bois, Renard Crabier

Spanish; Castilian: Perro Sabanero, Perro de Monte, Perro-zorro, Zorra Baya, Zorro, Zorro Cangrejero, Zorro Carbonero, Zorro Común, Zorro Patas Negras, Zorro Perruno, Zorro Sabanero, Zorro de Monte, Zorro-lobo, Zorro-perro

German: Maikong, Waldfuchs

Italian: Volpe Sciacallo

Portuguese: Cachorro-do-mato, Fusquinho, Graxaim, Graxaim-do-mato, Guancito, Lobete, Lobinho, Mata Virgem, Rabo Fofo, Raposa, Raposão

Justification

This species is listed as Least Concern as the Crab-eating Fox is relatively common throughout its range, occupying most habitats and although no estimates of population sizes are available, populations generally are considered stable.

Geographic Range Information

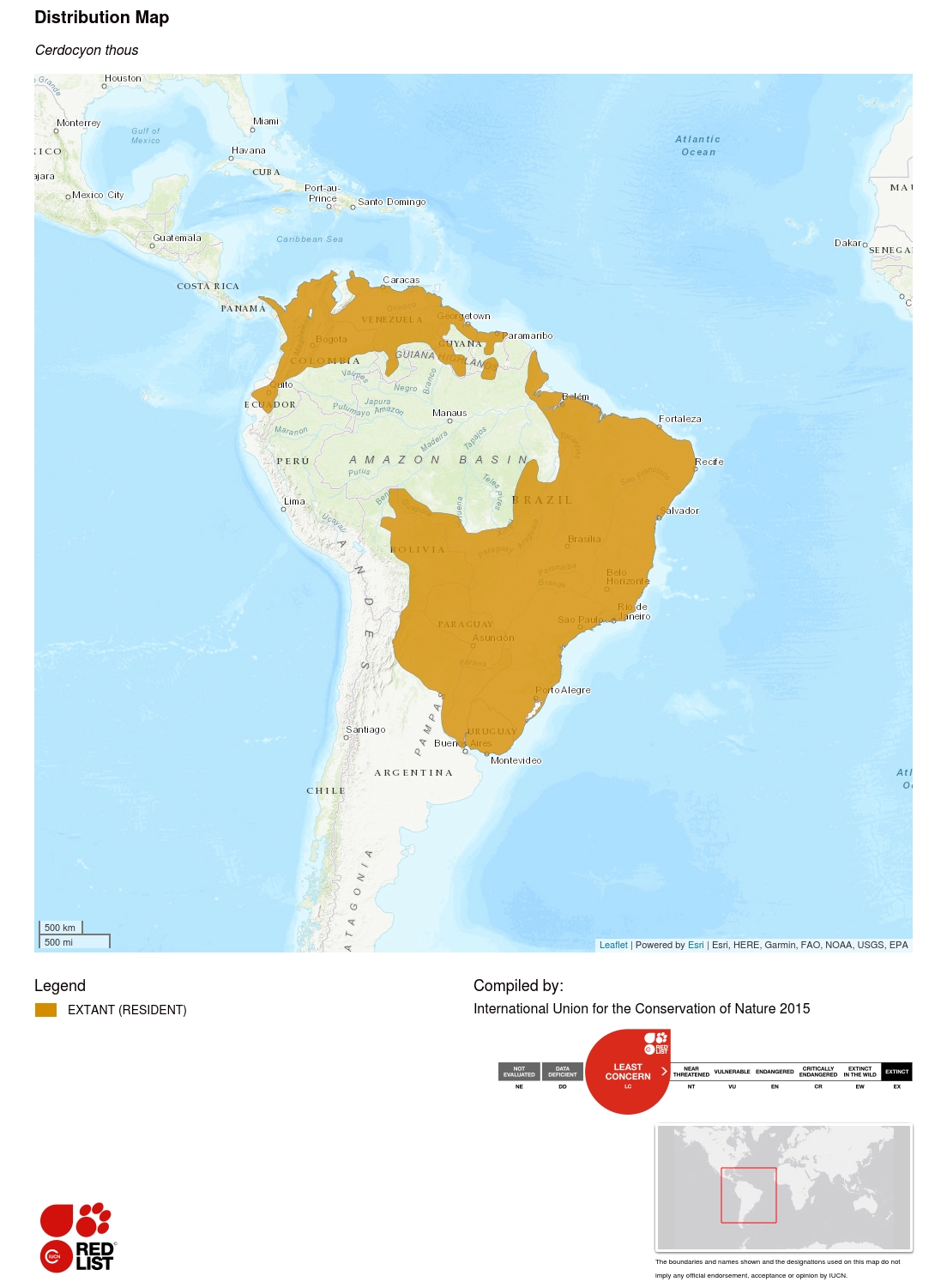

This species is relatively common throughout its range from the coastal and montane regions in northern Colombia and Venezuela, south to the provinces of Entre Ríos and adjacent northern Buenos Aires, Argentina (35°S); and from the eastern Andean foothills (up to 2,000 m asl) in Bolivia and Argentina (67°W) to the Atlantic forests of east Brazil. Its known central distribution in lowland Amazon forest is limited to areas northeast of the Rio Amazon and Rio Negro (2°S, 61°W), southeast of the Rio Amazon and Rio Araguaia (2°S, 51°W), and south of Rio Beni, Bolivia (11°S). Tejera et al. (1999) recorded the first documented evidence from Panama, and since then additional records have come to light from elsewhere in the eastern part of the country. In recent years, range extensions have been documented in Venezuela (Hladik-Barkoczy 2013), Brazil (de Thoisy et al. 2013), Argentina (Fracassi et al. 2010) and Colombia (Ramírez-Chavez and Pérez 2015; these authors also commented on presence in Ecuador).

Few records exist in Suriname and Guyana. Records in French Guyana (Hansen and Richard-Hansen 2000) have yet to be confirmed (Courtenay and Maffei 2004). The previous citation of its occurrence in Peru (Pacheco et al. 1995) has since been retracted by the authors (Courtenay and Maffei 2004).

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

The only population density estimate was produced in a coastal area of southern Brazil. Based on live capture-recapture data, a density of 0.78 individuals/km2 was estimated over an area of 8.9 km2 (Faria-Corrêa et al. 2009). No precise estimates of total population sizes are available, but populations generally are considered stable.

Habitat and Ecology Information

This species occupies most habitats including marshland, savanna, cerrado, caatinga, chaco-cerrado-caatinga transitions, scrubland, woodlands, dry and semi-deciduous forests, gallery forest, Atlantic forest, Araucaria forest, isolated savanna within lowland Amazon forest, and montane forest. There are records up to 3,000 m asl. It adapts well to deforestation, agricultural and horticultural development (e.g., sugarcane, eucalyptus, melon, pineapples, pastures) and habitats in regeneration. In the arid Chaco regions of Bolivia, Paraguay and Argentina, it is confined to woodland edge and more open areas used by the Pampas Fox.

Vegetative habitats are generally utilized in proportion to abundance, varying with social status and climatic season. Radio-tagged foxes in seasonally flooded savannas of Marajó, Brazil, predominated in wooded savanna (34%) and regeneration scrub (31%); low-lying savanna was "avoided", and areas of wooded savanna "preferred", more by senior than junior foxes and more in the wet season than dry season (Macdonald and Courtenay 1996). In the central llanos of Venezuela, fox home ranges similarly shift to higher ground in response to seasonal flooding, though are generally located in open palm savanna (68% of sightings) and closed habitats (shrub, woodlands, deciduous forest, 32%; Brady 1979, Sunquist et al. 1989). In Minas Gerais, Brazil, two radio-tagged foxes (one male, one female) in different territories were observed most often at the interface of livestock pasture and gallery forest ("vereidas"; 82%) and in eucalyptus/agricultural plantations (8%; Courtenay and Maffei 2004). In Saõ Paulo state, Brazil, although 42.9% of presence records were at less than 100 m from forest fragments, its occurrence was not related to any specific landscape variable (de Barros Ferraz et al. 2010). Similarly, in a protected area located in the southernmost part of Brazil (Rio Grande do Sul state) it was observed in all sampled habitats (Faria-Corrêa et al. 2009). Crab-eating Foxes were more frequently recorded in the thicker habitats, the gallery forests and the shrubland without cattle, in the Iberá wetlands of northeastern Argentina (Di Bitetti et al. 2009). Eighty-eight Crab-eating Fox specimens collected by the Smithsonian Venezuelan Project were taken from prairie and pasture (49%), deciduous and thorn forest (19%), evergreen forest (17%), and marshes, croplands and gardens (15%; Handley 1976 as cited in Cordero-Rodríguez and Nassar 1999).

Threats Information

The main potential threat, albeit localized, is from spill-over pathogenic infection from domestic dogs. In the Serra da Canastra National Park, Brazil, Crab-eating Foxes raid human refuse dumps in close company with unvaccinated domestic dogs along park boundaries (Courtenay and Maffei 2004).

Use and Trade Information

This species is of no direct commercial value as a furbearer due to the unsuitability of the fur which is coarse and short; however, pelts are sometimes traded as those of the South American Grey Fox in Argentina, and as those of the latter species and the Pampas Fox in Uruguay (Cravino et al. 1997, Courtenay and Maffei 2004). Current illegal trade is small as the probable consequence of low fur prices; in Paraguay, for example, no illegal fox pelts were confiscated from 1995 to 2000 (Courtenay and Maffei 2004).

Conservation Actions Information

Legislation

It is listed on CITES – Appendix II. In Argentina, the Crab-eating Fox was considered "not endangered" by the 1983 Fauna and Flora National Direction (resolution 144), and its exploitation and commercial use was forbidden in 1987 (Courtenay and Maffei 2004). There is no specific protective legislation for this species in any country, though hunting wildlife is officially forbidden in most countries. Generally, there is no specific pest regulatory legislation for the Crab-eating Fox, but it is strongly disliked locally as a pest of livestock (poultry and lambs) leading to illegal hunting and consequential sales of pelts. In some countries, pest control is limited by specific quotas (without official bounties), although the system is often ignored, abused, or not reinforced (Courtenay and Maffei 2004). In Uruguay, hunting permits have not been issued since 1989 on the basis that lamb predation by foxes is negligible (Cravino et al. 1997, 2000).

Presence in protected areas

It occurs in a large number of protected and unprotected areas across its geographical range.

Presence in captivity

It is apparently present in many zoos and private collections throughout South America where it generally breeds well.

Gaps in knowledge

Little is known of the population status of this species in lowland Amazon forest.