- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

South AmericaCulpeo Lycalopex culpaeus

culpeo - © Enrique Couve Montané

Amazonian Canids Working Group - Karen DeMatteo and Fernanda Michalski are the coordinators of the Amazonian Canids Working Group. This working group is focused on four species: the short-eared dog, crab-eating fox, bush dog, and South American foxes. Amazonian canids are similar to many carnivores worldwide whose long-term survival is threatened by a variety of direct and indirect threats, including habitat loss, expansion of hydroelectric dams, illegal hunting of prey, and diseases from domestic dogs.

ProjectsRelevant LinksReports / Papers- 2004 Status Survey & Convervation Action Plan - South America

- El manejo de zorros en la Argentina. Compatibilizando las interacciones entre la ganadería, la caza comercial y la conservación

- Effects of livestock on the feeding ecology of endemic culpeo foxes (Pseudalopex culpaeus smithersi) in central Argentina

- Activity patterns in sympatric carnivores in the Nahuelbuta Mountain Range, southern-central Chile (Zúñiga et al. 2016)

- Native-predator–invasive-prey trophic interactions in Tierra del Fuego: the beginning of biological resistance? (Castillo et al. 2017)

- Predation of livestock by puma (Puma concolor) and culpeo fox (Lycalopex culpaeus): numeric and economic perspectives (Gallardo et al. 2020)

- Sarcoptic mange: An emerging threat to Chilean wild mammals? (Montecino-Latorre et al. 2020)

Synonym: Pseudalopex culpaeus

English: Culpeo, Andean Fox

French: Culpeau

Spanish; Castilian: Culpeo, Lobo Andino, Zorro Andino, Zorro Colorado, Zorro Culpeo

German: Andenfuchs

Taxonomic Notes

Several recent molecular studies have provided support for a monophyletic assemblage of South American endemic canids (Lindblad-Toh et al. 2005, Perini et al. 2010), withChrysocyon and Speothos forming a sister-clade to the monophyletic South American foxes and Atelocynus. On the basis of morphology, Zunino et al. (1995) reviewed previous work and also supported clustering species within the two previous paraphyletic genera (Pseudalopex, Lycalopex) into a single monophyletic genus. They further argued that Lycalopex had priority over Pseudalopex, subsequently also supported by Zrzavý et al. (2004: 324). The only outstanding question would have been whether Dusicyon would have been a more appropriate name, since Perini et al. (2010) reported a close relationship between L. culpaeus and Dusicyon. However, we now know that Dusicyon is far outside this clade (Slater et al. 2009, Austin et al. 2013). Based on this evidence, the genus Lycalopex is used over Pseudalopex for all South American foxes, following Wozencraft's (2005) earlier treatment.

Justification

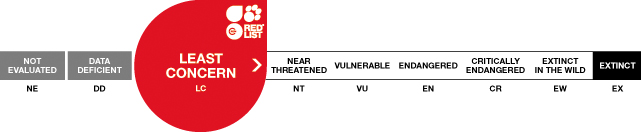

The Culpeo is distributed from the Andes and hilly regions of South America, ranging down to the Pacific shoreline in the desert of northern Chile and Argentine Patagonia. Culpeos appear to withstand intense hunting levels and still maintain viable regional populations. When hunting pressure is reduced, populations usually can recover quickly. However, it appears that the combined effects of hunting and interspecific competition/predation with Pumas (Puma concolor) are producing a marked reduction in population numbers in some parts of the range in southern Argentina. At present, there is no reason to believe the species is declining at a rate sufficient to warrant listing in a threatened category and is listed as Least Concern.

Geographic Range Information

The Culpeo is distributed along the Andes and hilly regions of South America from Nariño and Putumayo Departments of south-west Colombia in the north (Jiménez et al. 1995, Ramírez-Chaves et al. 2013; records from departments further north are dubious) to Tierra del Fuego in the south (Markham 1971, Redford and Eisenberg 1992). It ranges down to the Pacific shoreline in the desert of northern Chile (Mann 1945, Jiménez and Novaro 2004), south to about Valdivia (Osgood 1943) and then again in Magallanes. On the eastern slopes of the Andes, the Culpeo is found in Argentina from Jujuy Province in the North, reaching the Atlantic shoreline from Río Negro and southwards. This extended eastward distribution is relatively recent and was apparently favoured by sheep ranching, increased availability of exotic prey and extirpation of Puma (Crespo and De Carlo 1963, Novaro 1997a, Novaro and Walker 2005). However, in the last 10-15 years the shrinking of sheep production in Argentine Patagonia has facilitated Puma recolonization. The probable increase in predation or competitive exclusion by Pumas in turn appears to have caused declines in Culpeo populations (Travaini et al. 2007, A. Travaini pers. comm. 2015).

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

Due to conflicts with humans (i.e., preying upon poultry and livestock, Crespo and De Carlo 1963, Bellati and von Thüngen 1990, Lucherini and Merino 2008) and because of its value as a furbearer, the Culpeo has been persecuted throughout its range for many decades (Jiménez 1993, Novaro 1995). Thus, current population numbers may be the result of past and present hunting pressure and food availability. The introduction of exotic prey species such as European Hares (Lepus europaeus) and rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus), as well as small-sized livestock into Chile and Argentina ca. 100 years ago, probably led to increases in the distribution and abundance of Culpeos, and facilitated their expansion towards the lowlands in eastern Argentina (Crespo and De Carlo 1963, Crespo 1975, Jiménez 1993, Jaksic 1998, Novaro et al. 2000a). The recent observation that the comeback of Pumas in Patagonia may be affecting negatively its abundance suggests that a reduction of intraguild competition/predation had also favoured this expansion in range. Currently, Culpeos range over a much wider area in Patagonia than previously. Likewise, in several areas of the desert of northern Chile, recent mining activities provide the Culpeo with resources such as food, water and shelter that were in much shorter supply in the past, and hence have changed their local distribution and abundance (Jiménez and Novaro 2004).

Culpeos appear to withstand intense hunting levels as shown by fur harvest data from Argentina and still maintain viable regional populations (Novaro 1995). However, this may only be possible through immigration from neighbouring unexploited areas that act as refugia (Novaro 1995). The Culpeo population in Neuquén Province in north-west Patagonia for example, appears to function as a source-sink system in areas where cattle and sheep ranches are intermixed (Novaro 1997b, Novaro et al. 2005). Cattle ranches where no hunting occurs supply disperser foxes that repopulate sheep ranches with intense hunting. Changes in sex ratio may be another mechanism that allows Culpeo populations to withstand intense hunting (Novaro 1995). Furthermore, large litter size and early maturity (Crespo and De Carlo 1963) could explain the Culpeo's high resilience to hunting.

When hunting pressure is reduced, Culpeo populations usually can recover quickly (Crespo and De Carlo 1963). This increase was observed at the Chinchilla National Reserve (Jiménez 1993) and at Fray Jorge National Park (Meserve et al. 1987, Salvatori et al. 1999), both in north-central Chile. Culpeo densities also have increased in many areas of Argentine Patagonia following the reduction of fur prices and hunting pressure in the late 1980s and early 1990s (Novaro 1997b, Novaro and Walker 2005). An exception to this response is the Culpeo population in Tierra del Fuego, where its populations are still declining in spite of several years of reduced hunting pressure (N. Loekemeyer and A. Iriarte, in Jiménez and Novaro 2004).

Estimates from intensive trapping by Crespo and De Carlo (1963) provided a density of 0.7 individuals/km² for north-west Patagonia, Argentina. Thirty years later, Novaro et al. (2000b), using line transects, reported densities of 0.2–1.3 individuals/km² for the same area. In north-central Chile, the ecological density of culpeos in ravines was 2.6 individuals/km², whereas the crude density (throughout the study site) was 0.3 individuals/km² (Jiménez 1993). In Torres del Paine, a crude density of 1.3 individuals/km² was reported based on sightings (J. Rau, in Jiménez and Novaro 2004). Interestingly, a later estimate for the same area, based on telemetry, rendered an ecological density of 1.2 individuals/km² (Johnson 1992, in Jiménez 1993).

Based on radio telemetry, sightings and abundance of faeces, Salvatori et al. (1999) concluded that Culpeos respond numerically to a decline in the availability of their prey in north-central Chile. Earlier, based on abundance of faeces, Jaksic et al. (1993) reached the same conclusion for the same Culpeo population. In contrast, Culpeos (not distinguished from sympatric Chillas) did not show a numerical or a functional response during a decline of their main prey at another site in north-central Chile (Jaksic et al. 1992).

Habitat and Ecology Information

Throughout its wide distribution, the Culpeo uses many habitat types ranging from rugged and mountain terrain, deep valleys and open deserts, scrubby pampas, sclerophyllous matorral, to broad-leaved temperate southern beech forest in the south. The Culpeo uses all the range of habitat moisture gradients from the driest desert to the broad-leaved rainforest. In the Andes of Peru, Chile, Bolivia and Argentina, the Culpeo reaches elevations of up to 4,800 m (Redford and Eisenberg 1992, Romo 1995, Jiménez and Novaro 2004, Tellaeche et al. 2014). Redford and Eisenberg (1992) placed the Culpeo in the coldest and driest environments of South America relative to other South American canids.

Threats Information

Main threats to Culpeos have been hunting and trapping for fur (although trade has decreased in the last decade) and persecution to reduce predation on livestock and poultry (Travaini et al. 2000, Lucherini and Merino 2008). Although illegal, the use of poison to reduce or prevent livestock losses caused by Culpeos is still widespread in some parts of its range, including remote areas of the high Andes (García Brea et al. 2010, M. Lucherini pers. comm. 2015.). Habitat loss does not appear to be an important threat to this species. Predation by feral and domestic dogs may be important in some areas (Novaro 1997b).

Use and Trade Information

Until the early 1990s, the main cause of mortality was hunting and trapping for fur (Miller and Rottmann 1976, Novaro 1995). During 1986, in excess of 2,100 fox skins (Culpeo and Chilla) were exported from Chile (Iriarte et al. 1997). An average of 4,600 Culpeo pelts were exported annually from Argentina between 1976 and 1982, with a peak of 8,524 in 1977. Legal exports declined to an average of approximately 1,000 between 1983 and 1996 with peaks of 2,421 in 1990 and 4,745 in 1996 and have been negligible since 1997 (Novaro 1995, Jiménez and Novaro 2004).

Conservation Actions Information

Legislation

Included on CITES – Appendix II.

The Argentine legislation about Culpeos is contradictory. Culpeos were considered "Endangered" by a 1983 decree of the Argentine Wildlife Board (Dirección de Fauna y Flora Silvestres), due to the numbers of Culpeo pelts traded during the 1970s and early 1980s. However, trade at the national level and export of Culpeo pelts was legal during that entire period and currently remains legal. Culpeos are legally hunted in 6 Argentine provinces and a bounty system is in place in two of them. The Culpeo's endangered status has never been revised in spite of marked changes in the fur trade and reports from monitoring programmes. However, it has been listed as Near Threatened in the most recent national Red List (Lucherini and Zapata 2012). The Tierra del Fuego population has been legally protected since 1985.

In Peru, the Culpeo is not considered endangered, but permits are issued by the government to hunt individuals depredating on livestock (D. Cossios pers. comm. 2015). Similarly, in Chile, where the species is listed as Least Concern, the Hunting of Culpeos is illegal (since 1980), but permits may be obtained for predator control (A. Iriarte and J. Jimenez, pers. comm. 2015). In Bolivia, although the fur export was banned in 1986 and hunting is illegal, Culpeos are commonly killed to reduce predation on livestock (Tarifa 1996, L. Pacheco pers. comm. 2015).

The Argentine Wildlife Board is starting to develop a management plan for canids that will include the Culpeo. Five regional workshops that included wildlife agency officials from provincial governments, wildlife traders, conservationists, and scientists have been held in Argentine Patagonia to coordinate efforts to manage Culpeo populations in a sustainable manner and reduce sheep predation (Funes et al. 2006).

Presence in protected areas

In Chile, the Culpeo occurs in the large majority of protected areas distributed throughout the country, encompassing all the habitats where it can be found. However, only 14% are large enough to support viable populations. In Argentina, the species occurs in 12 national parks and several provincial reserves, the majority of which probably support viable populations. In Peru, Culpeos occur in 18 (D. Cossios pers. comm. 2015) and in Bolivia in nine (Wallace et al. 2010, L. Pacheco pers. comm. 2015) of each country's national system of protected areas.

Presence in captivity

The Culpeo is common in zoos throughout Chile and Argentina.