- South America

- Central & North America

- Europe & North/Central Asia

- Sub-Saharan Africa

- North Africa & the Middle East

- South Asia

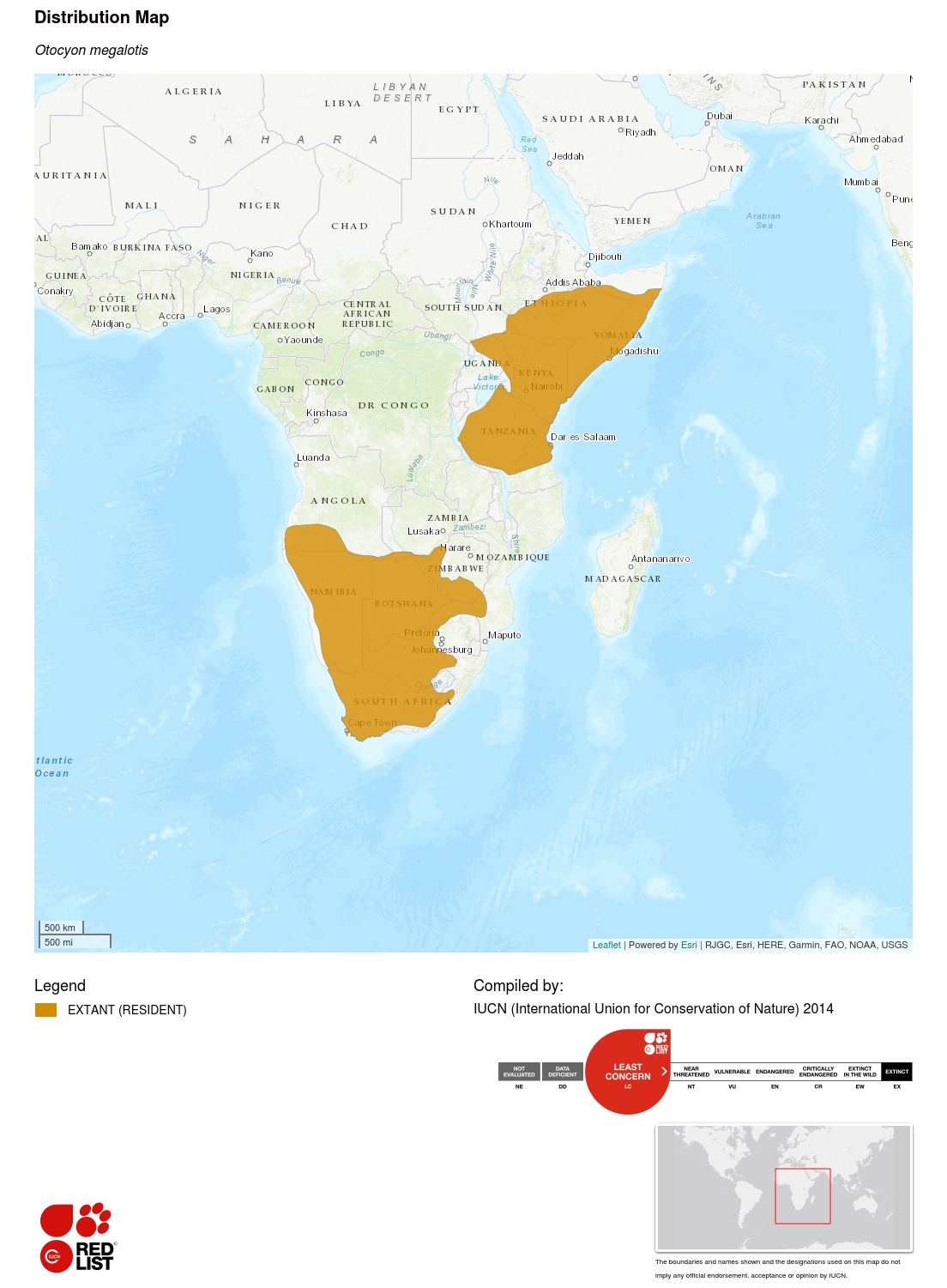

Sub-Saharan AfricaBat-eared fox Otocyon megalotis

bat-eared foxes - © Chris and Tilde Stuart

Relevant LinksReports / PapersOther NamesEnglish: Bat-eared Fox

French: l 'Otocyon

Afrikaans: Bakoorjakkals, Bakoorvos, Draaijakkals

German: Löffelhund

Justification

The Bat-eared Fox occurs in two discrete subpopulations in eastern and southern Africa. The species is widespread and is common in conservation areas, becoming uncommon in arid areas and on farms in South Africa where they are occasionally persecuted. There are no major threats believed to be resulting in any major range-wide declines.

Geographic Range Information

The Bat-eared Fox has a disjunct distribution range, occurring across the arid and semi-arid regions of eastern and southern Africa in two discrete populations (representing each of the known subspecies) separated by about 1,000 km. Subspecies O. m. virgatus ranges from southern Sudan, Ethiopia and Somalia down through Uganda and Kenya to south-western Tanzania; O. m. megalotis occurs from Angola through Namibia and Botswana to Mozambique and South Africa (Coetzee 1977; Kingdon 1977; Nel and Maas 2004, 2013; Skinner and Chimimba 2005). There are no confirmed records from Zambia (Ansell 1978). The two ranges were probably connected during the Pleistocene (Coe and Skinner 1993). This disjunct distribution is similar to that of other endemic, xeric species e.g., Aardwolf Proteles cristatus and Black-backed Jackal Canis mesomelas. Range extensions in southern Africa documented in recent years (e.g., Stuart 1981, Marais and Griffin 1993) have been linked to changing rainfall patterns (MacDonald 1982).

Population trend:Stable

Population Information

The species is common in conservation areas in southern and eastern Africa, becoming uncommon in arid areas and on farms in South Africa where they are occasionally persecuted. Within a circumscribed habitat, numbers can fluctuate from abundant to rare depending on rainfall, food availability (Waser 1980, Nel et al. 1984), breeding stage and disease (Maas 1993a,b; Nel 1993). Recorded densities include 0.7-14/km² in the Kalahari (Nel et al. 1984) and 0.3-1.0 / km² in the Serengeti (Hendrichs 1972).

Habitat and Ecology Information

In southern Africa, the prime habitat is mainly short-grass plains and areas with bare ground (Mackie and Nel 1989), but they are also found in open scrub vegetation and arid, semi-arid or winter rainfall (fynbos or Cape macchia) shrub lands, and open arid savanna. The range of both subspecies overlaps almost completely with that of Hodotermes and Microhodotermes, termite genera prevailing in the diet (Mackie and Nel 1989, Maas 1993a). In the Serengeti, they are common in open grassland and woodland boundaries but not short-grass plains (Lamprecht 1979, Malcolm 1986); harvester termite (H. mossambicus) foraging holes and dung from migratory ungulates are more abundant in areas occupied by Bat-eared Foxes, while grass is shorter and individual plants are more widely spaced (Maas 1993a).

Threats Information

There are no major threats, but they are subject to subsistence hunting for skins or because they are perceived as being predators of small livestock. Populations fluctuate due to disease (especially rabies and canine distemper, which can cause short-term drastic declines in populations) or drought (which depresses insect numbers).

Use and Trade Information

Commercial use is very limited, but winter pelts are valued and sold as blankets. They are also sold as hunting trophies in South Africa.

Conservation Actions Information

The species is not included in the CITES Appendices. It is present in a number of protected areas across its range (see Nel and Maas 2004, 2013).

Bat-eared Foxes are kept in captivity in North America, Europe, South Africa and Asia, although never in large numbers. A Bat-eared Fox European StudBook was established at Banham Zoo in 2011 and an AZA Studbook has been established at Peoria Zoo in Illinois (2012/2013) (M. Woolham pers. comm. 2013). Importations have occurred throughout the history of the captive population despite successful captive breeding since 1970. Bat-eared Foxes can coexist well with other species and are frequently seen in African plains exhibits at zoos.

Little is known about dispersal of young and the formation of new breeding pairs. The causal factors for differences in home range size in different localities, group size and changes in density as a function of food availability are poorly known. In the Serengeti, behavioural evidence on group and pair formation and the existence of 'super families', consisting of one male and up to three closely related breeding females, raises interesting questions about regular inbreeding between males and their daughters from several generations (see Maas 1993a).